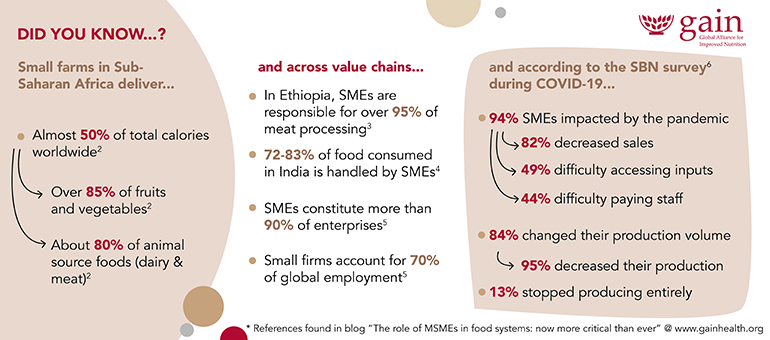

From empty supermarket shelves to vegetables thrown away uneaten due to shutdowns, COVID-19 has revealed many vulnerabilities in global and local food systems. Not only that, but the pandemic has also reminded us of the essential role nutrition and food security play in boosting immunity and resistance to disease. Around the world, micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), play a critical role within those food systems, particularly for low-income consumers in low-and middle- income countries (LMIC) (see Figure1).

Unfortunately, SMEs within the food system in LMICs face many challenges. Starting a business and trying to comply with regulations is difficult and time-consuming. Accessing financing to weather downturns or expand and innovate can be an even greater challenge. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, there is a USD 100 billion lending gap for agri-food SMEs (1) . On top of this, food system SMEs have recently been hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and all associated control measures. A recent survey of 363 agri-food SMEs in 17 countries by GAIN, the SUN Businesses Network, and the World Food Programme showed that 94% reported being impacted by the pandemic (see Figure 1). Nearly all responding firms had taken action to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on their business or to protect their employees, and about one third reported downsizing their workforce. Similar results have been found in surveys fielded by other organisations.

Figure 1. Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) around the world play critical roles within food systems. SMEs have been hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures. © GAIN

These quantitative results are confirmed in the experiences of individual businesses. A case in point is Farmfresh Food Company, which typically sells its nutritious precooked beans across Rwanda and East Africa. COVID-19 left it constrained by restrictions imposed at borders. While other businesses closed, the company remained open because they believed that the crisis might open new market opportunities and were keen to find opportunities for innovation. During an interview with Marie Claire Nyirankundizane, the Acting Managing Director at FarmFresh, she explained that schools purchased much of their production but are now closed. “We are therefore exploring other market opportunities. We’re focusing our marketing and distribution on Kigali only. And we’re sending more of our products to supermarkets and to distributors who sell through online portals.” In contrast, Rwanda’s Lakeside Ltd., which produces fish, faced major challenges that forced the company to reduce its activities. They could not get machinery serviced, customers were not paying their debts as planned, a container of imported fish feed remains stuck on the Zambian border, and their sales income has fallen almost to zero. In addition, they lost 100,000 catfish fingerlings - a loss that jeopardised the future of the company and that of other fish farmers they supply. Roger Shaw, the firm’s Managing Director, told GAIN that apart from closing the shop, they took other measures to manage the shock of COVID-19, such as sending staff home on full pay and furloughing non-essential workers.

Similar experiences have been seen in many other countries, such as Pakistan - where SMEs represent more than 90% of enterprises and dominate across food supply chains. For example, Pakistan’s small-scale dairy producers and processors, which often sell their milk through informal channels, were impacted early on in the pandemic by restaurant closures and consumer reticence to buy fresh milk and milk products from informal chains. The result was significant wastage of milk initially. Another hard-hit sector was agricultural input providers: Pakistan imports most of its vegetable seed from China, the US, and Thailand. The effects of the pandemic on production in these countries, a severe reduction in available freight transport, and long delays in port clearance and testing led to interruptions and shortages. Pakistani SMEs have not taken these challenges passively: some dairy producers ventured into processing and others attempted to diversify their customer base, while input SMEs decentralised their distribution and stocking to better meet local demand. There were also some positive business impacts of lockdown for those firms well-poised to overcome the sudden challenges. For example, tech-enabled retail start-up SMEs that buy from farmers and deliver directly to consumers reported large increases in sales.

A person stops in front of several vegetable stands. © Pexels/ Hugo Heimendinger

Although some food system SMEs around the world have adapted admirably, the need to support them is greater than the challenges most of them are facing. Helping SMEs navigate the current crisis, seize emerging opportunities, and strengthen future food system resilience will require both short- and long-term initiatives. To overcome the immediate pressures, short-term emergency financing and targeted technical assistance are necessary. Certain government and international organisations have moved fast to provide emergency funding to help businesses. However, in many LMICs, the capacity of domestic governments to provide financing is limited. The development finance sector and non-governmental organisations can contribute towards emergency efforts. GAIN’s own experience has shown the importance of tailored assistance to SMEs during crises. In Mozambique, for example, GAIN’s Marketplace for Nutritious Foods programme supported SMEs to rebuild in the aftermath of devastating cyclones in 2019.

Looking beyond the immediate challenges posed by COVID-19, we should learn from this crisis and put in place mechanisms and programmes that will help SMEs overcome similar shocks in the future, enhancing the resilience of local and global food systems. To this end, it is important to support the long-term development of SMEs. As noted above, one major barrier to SME development is their lack of access to affordable and timely growth capital. SMEs, particularly those in LMICs, struggle to access long-term finance, which limits their ability to expand their operations, train staff, and introduce new machinery and technologies. In parallel, technical assistance is needed to improve the commercial performance of SMEs, increase the nutritional value and safety of the foods they produce, and promote sustainable practices by reducing food loss. To help lead the way in this space, GAIN’s Nutritious Foods Financing Facility (N3F) is seeking to provide agri-food SMEs in Africa with financial and technical assistance. The N3F will provide working and growth capital alongside tailored technical assistance to SMEs operating in nutritious value chains in Africa. The goal is to help them scale their businesses, amplify their impact, and build a more resilient food system.

At GAIN, we have long recognised that SMEs are critical actors in ensuring access to food and nutrition security worldwide, particularly for the poorest consumers, and should be championed and supported. SMEs need to think about innovation, which is in itself disruption, while being concerned about disruption in their own current model. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the degree to which this is needed and the urgency with which it must happen. SME owners and employees have been working diligently and innovating to adapt to a new reality without ceasing to provide consumers with safe, nutritious foods. We need to continue to support them, to ensure they can continue to deliver on that crucial role.