‘Ultra-processed food’ (UPF) has been the nutrition buzzword of the past few years, making its way from scientific research into headlines and policy debates. These foods, commonly defined as industrial food formulations made with ingredients rarely used in home cooking, make up a shockingly large share of diets and have been associated with various negative health effects – but their role remains complicated and contested. At the recent Stockholm Food Forum, I joined this debate, participating on a panel discussion on the topic.

So, after an invigorating session and dozens of side conversations, how do I see these foods?

Certainly, they are a major part of our diets and food systems: in the highest-consuming countries, like the US and UK, over half of calories come from these foods – and an even higher share for children and adolescents. And their consumption has been associated with increased risk of a staggering number and diversity of adverse health outcomes, from diabetes, heart disease, and Crohn’s disease to various cancers and depression.

Yet the definition is contested. For example, some argue it’s difficult to apply in practice, while others note that the category is very large and covers a diversity of foods with widely divergent properties, from chocolate bars to yoghurts, and thus might not be very helpful for guiding researchers, consumers, or policymakers. Examining data on health effects also shows very different results across UPF subgroups, with some, like sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats, consistently associated with bad outcomes, while others, like whole-grain breads and cereals or dairy products, show no such patterns – even sometimes beneficial associations. This very valid scientific debate is muddled by some with vested interests—such as certain industry lobbyists—purposefully trying to create uncertainty to discredit the underlying science (and thus reduce risks of regulation or public backlash that might harm their businesses).

The topic Is a hard one for scientists to study, since many of the negative health effects associated with diets take years to manifest, but one can only randomize and control people’s diets (the research gold standard) in very short-term studies (which are also very resource intensive to do!) Instead, most research needs to rely on observational studies that collect data on many people and look for statistical associations between foods reported consumed and health outcomes. Even the best such studies have weaknesses, such as misreporting by respondents and not being able to control for every non-diet factor that could affect health. But again, a valid debate on methods, such as whether confounding has been sufficiently controlled for, gets muddled by those with vested interests in discrediting the science.

It's clear that a large share of UPFs have limited positive role in the diet; many shouldn’t even be on store shelves. But the whole category is not without positive contributions to ensuring access to healthy, sustainable diets for all. For example, many UPFs have extended shelf lives, which can make foods more accessible in remote areas, places where cold chains don’t reach, and for those who lack refrigerators; others provide benefits in terms of food safety, convenience, waste reduction, and added nutrients. Many plant-based meat analogue products are UPFs, but they have considerable potential to help reduce meat consumption to improve food systems’ environmental sustainability.

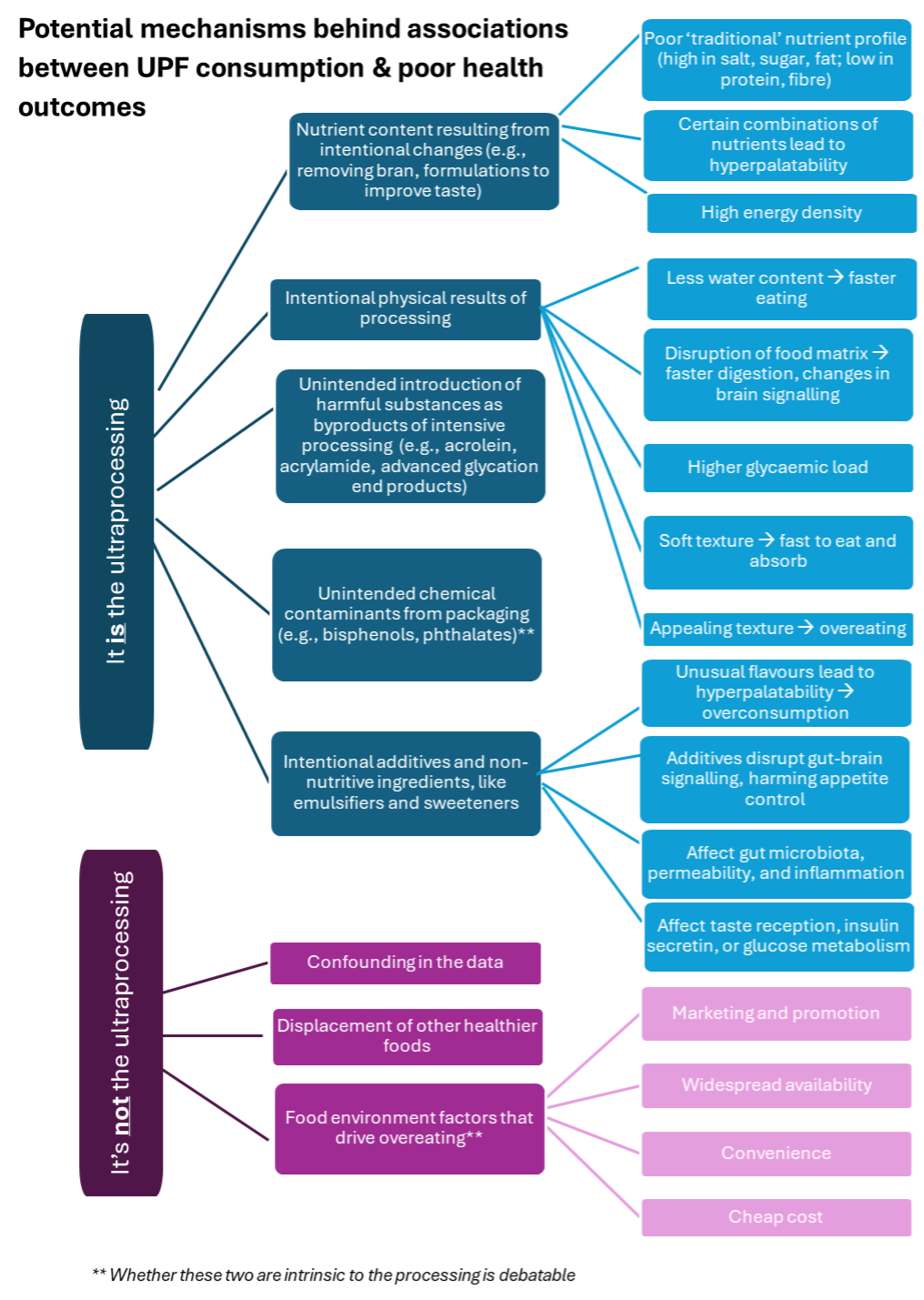

But providing more specific guidance on which UPFs should be strongly discouraged (or even banned), which are acceptable, and whether there are opportunities for beneficial reformulation requires clarifying the mechanisms driving the observed negative effects. My attempt to understand the many that have been proposed is shown in the figure below. I expect it’s probably a combination of most of these, depending on the specific food in question. (Though given the results of prior research, including large observational cohort studies and multiple RCTs, it’s almost certainly not only confounding, traditional nutrient content, food environment, or displacement – though these may all play some role.)

Overall, where I’ve landed is that the concept of UPFs has been valuable on several fronts: helping get away from the ‘nutrient reductionism’ of the 80s and 90s (where foods were reformulated focusing just on certain ‘bad’ nutrients, like fat or carbs or sugar); reminding us that most things that look like junk food are indeed junk food; making us think about the broader food system and the processes and incentives that shape the food that shows up on our plates; spurring novel research areas; and sparking renewed public and policy interest in healthy eating.

But, as a category, ‘UPF’ has probably outgrown its usefulness in guiding research, policy, and consumer decisions. There is a need to more towards more nuanced definitions that focus in on the subcategories of foods with the least benefit and greatest harm – and that elucidate the mechanisms behind them, which is needed to guide evidence-based policymaking.